File Format

Documentation about the Parquet File Format.

This file and the thrift definition should be read together to understand the format.

4-byte magic number "PAR1"

<Column 1 Chunk 1>

<Column 2 Chunk 1>

...

<Column N Chunk 1>

<Column 1 Chunk 2>

<Column 2 Chunk 2>

...

<Column N Chunk 2>

...

<Column 1 Chunk M>

<Column 2 Chunk M>

...

<Column N Chunk M>

File Metadata

4-byte length in bytes of file metadata (little endian)

4-byte magic number "PAR1"

In the above example, there are N columns in this table, split into M row

groups. The file metadata contains the locations of all the column chunk

start locations. More details on what is contained in the metadata can be found

in the Thrift definition.

File metadata is written after the data to allow for single pass writing.

Readers are expected to first read the file metadata to find all the column

chunks they are interested in. The columns chunks should then be read sequentially.

The format is explicitly designed to separate the metadata from the data. This

allows splitting columns into multiple files, as well as having a single metadata

file reference multiple parquet files.

1 - Configurations

Row Group Size

Larger row groups allow for larger column chunks which makes it

possible to do larger sequential IO. Larger groups also require more buffering in

the write path (or a two pass write). We recommend large row groups (512MB - 1GB).

Since an entire row group might need to be read, we want it to completely fit on

one HDFS block. Therefore, HDFS block sizes should also be set to be larger. An

optimized read setup would be: 1GB row groups, 1GB HDFS block size, 1 HDFS block

per HDFS file.

Data Page Size

Data pages should be considered indivisible so smaller data pages

allow for more fine grained reading (e.g. single row lookup). Larger page sizes

incur less space overhead (less page headers) and potentially less parsing overhead

(processing headers). Note: for sequential scans, it is not expected to read a page

at a time; this is not the IO chunk. We recommend 8KB for page sizes.

2 - Extensibility

There are many places in the format for compatible extensions:

- File Version: The file metadata contains a version.

- Encodings: Encodings are specified by enum and more can be added in the future.

- Page types: Additional page types can be added and safely skipped.

3 - Metadata

There are two types of metadata: file metadata, and page header metadata.

All thrift structures are serialized using the TCompactProtocol. The full

definition of these structures is given in the Parquet

Thrift definition.

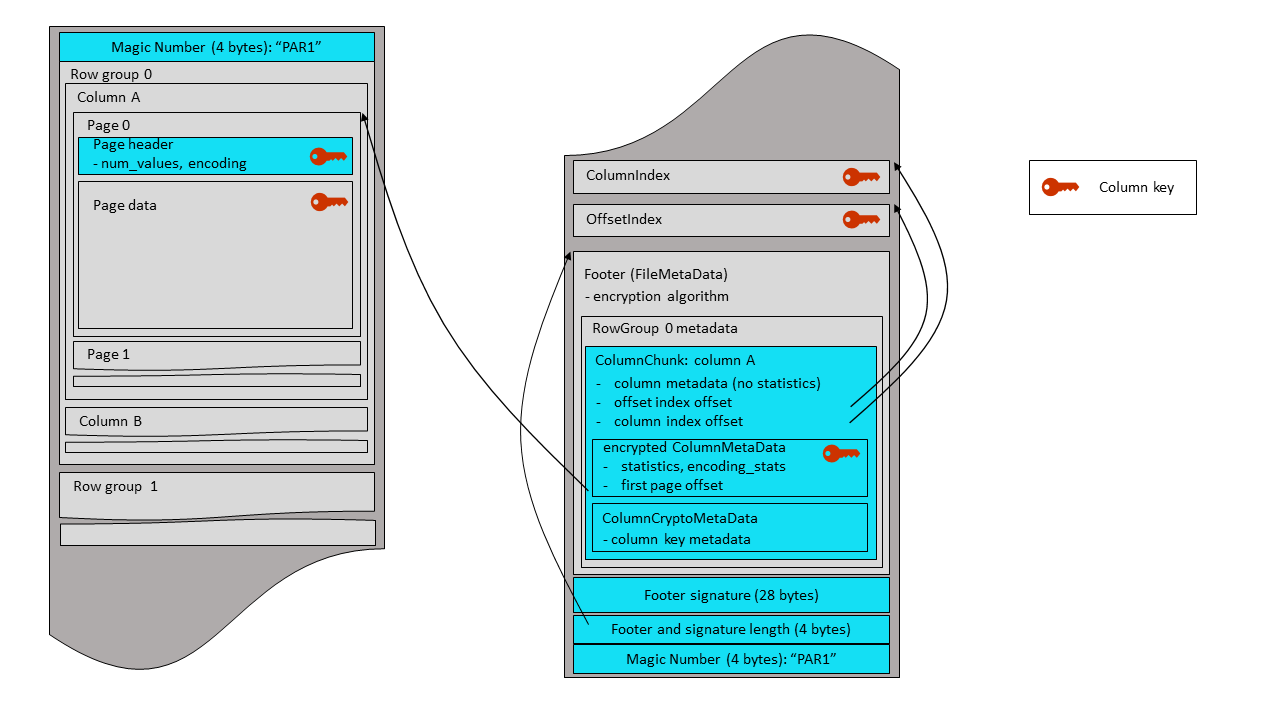

In the diagram below, file metadata is described by the FileMetaData

structure. This file metadata provides offset and size information useful

when navigating the Parquet file.

Page header metadata (PageHeader and children in the diagram) is stored

in-line with the page data, and is used in the reading and decoding of data.

4 - Types

The types supported by the file format are intended to be as minimal as possible,

with a focus on how the types effect on disk storage. For example, 16-bit ints

are not explicitly supported in the storage format since they are covered by

32-bit ints with an efficient encoding. This reduces the complexity of implementing

readers and writers for the format. The types are:

- BOOLEAN: 1 bit boolean

- INT32: 32 bit signed ints

- INT64: 64 bit signed ints

- INT96: 96 bit signed ints (deprecated; only used by legacy implementations)

- FLOAT: IEEE 32-bit floating point values

- DOUBLE: IEEE 64-bit floating point values

- BYTE_ARRAY: arbitrarily long byte arrays

- FIXED_LEN_BYTE_ARRAY: fixed length byte arrays

4.1 - Logical Types

Logical types are used to extend the types that parquet can be used to store,

by specifying how the primitive types should be interpreted. This keeps the set

of primitive types to a minimum and reuses parquet’s efficient encodings. For

example, strings are stored as byte arrays (binary) with a UTF8 annotation.

These annotations define how to further decode and interpret the data.

Annotations are stored as LogicalType fields in the file metadata and are

documented in LogicalTypes.md

5 - Nested Encoding

To encode nested columns, Parquet uses the Dremel encoding with definition and

repetition levels. Definition levels specify how many optional fields in the

path for the column are defined. Repetition levels specify at what repeated field

in the path has the value repeated. The max definition and repetition levels can

be computed from the schema (i.e. how much nesting there is). This defines the

maximum number of bits required to store the levels (levels are defined for all

values in the column).

Two encodings for the levels are supported BIT_PACKED and RLE. Only RLE is now used as it supersedes BIT_PACKED.

6 - Bloom Filter

Problem statement

In their current format, column statistics and dictionaries can be used for predicate

pushdown. Statistics include minimum and maximum value, which can be used to filter out

values not in the range. Dictionaries are more specific, and readers can filter out values

that are between min and max but not in the dictionary. However, when there are too many

distinct values, writers sometimes choose not to add dictionaries because of the extra

space they occupy. This leaves columns with large cardinalities and widely separated min

and max without support for predicate pushdown.

A Bloom filter is a compact data structure that

overapproximates a set. It can respond to membership queries with either “definitely no” or

“probably yes”, where the probability of false positives is configured when the filter is

initialized. Bloom filters do not have false negatives.

Because Bloom filters are small compared to dictionaries, they can be used for predicate

pushdown even in columns with high cardinality and when space is at a premium.

Goal

Enable predicate pushdown for high-cardinality columns while using less space than

dictionaries.

Induce no additional I/O overhead when executing queries on columns without Bloom

filters attached or when executing non-selective queries.

Technical Approach

The section describes split block Bloom filters, which is the first

(and, at time of writing, only) Bloom filter representation supported

in Parquet.

First we will describe a “block”. This is the main component split

block Bloom filters are composed of.

Each block is 256 bits, broken up into eight contiguous “words”, each

consisting of 32 bits. Each word is thought of as an array of bits;

each bit is either “set” or “not set”.

When initialized, a block is “empty”, which means each of the eight

component words has no bits set. In addition to initialization, a

block supports two other operations: block_insert and

block_check. Both take a single unsigned 32-bit integer as input;

block_insert returns no value, but modifies the block, while

block_check returns a boolean. The semantics of block_check are

that it must return true if block_insert was previously called on

the block with the same argument, and otherwise it returns false

with high probability. For more details of the probability, see below.

The operations block_insert and block_check depend on some

auxiliary artifacts. First, there is a sequence of eight odd unsigned

32-bit integer constants called the salt. Second, there is a method

called mask that takes as its argument a single unsigned 32-bit

integer and returns a block in which each word has exactly one bit

set.

unsigned int32 salt[8] = {0x47b6137bU, 0x44974d91U, 0x8824ad5bU,

0xa2b7289dU, 0x705495c7U, 0x2df1424bU,

0x9efc4947U, 0x5c6bfb31U}

block mask(unsigned int32 x) {

block result

for i in [0..7] {

unsigned int32 y = x * salt[i]

result.getWord(i).setBit(y >> 27)

}

return result

}

Since there are eight words in the block and eight integers in the

salt, there is a correspondence between them. To set a bit in the nth

word of the block, mask first multiplies its argument by the nth

integer in the salt, keeping only the least significant 32 bits of

the 64-bit product, then divides that 32-bit unsigned integer by 2 to

the 27th power, denoted above using the C language’s right shift

operator “>>”. The resulting integer is between 0 and 31,

inclusive. That integer is the bit that gets set in the word in the

block.

From the mask operation, block_insert is defined as setting every

bit in the block that was also set in the result from mask. Similarly,

block_check returns true when every bit that is set in the result

of mask is also set in the block.

void block_insert(block b, unsigned int32 x) {

block masked = mask(x)

for i in [0..7] {

for j in [0..31] {

if (masked.getWord(i).isSet(j)) {

b.getWord(i).setBit(j)

}

}

}

}

boolean block_check(block b, unsigned int32 x) {

block masked = mask(x)

for i in [0..7] {

for j in [0..31] {

if (masked.getWord(i).isSet(j)) {

if (not b.getWord(i).setBit(j)) {

return false

}

}

}

}

return true

}

The reader will note that a block, as defined here, is actually a

special kind of Bloom filter. Specifically it is a “split” Bloom

filter, as described in section 2.1 of Network Applications of Bloom

Filters: A

Survey. The

use of multiplication by an odd constant and then shifting right is a

method of hashing integers as described in section 2.2 of

Dietzfelbinger et al.’s A reliable randomized algorithm for the

closest-pair

problem.

This closes the definition of a block and the operations on it.

Now that a block is defined, we can describe Parquet’s split block

Bloom filters. A split block Bloom filter (henceforth “SBBF”) is

composed of z blocks, where z is greater than or equal to one and

less than 2 to the 31st power. When an SBBF is initialized, each block

in it is initialized, which means each bit in each word in each block

in the SBBF is unset.

In addition to initialization, an SBBF supports an operation called

filter_insert and one called filter_check. Each takes as an

argument a 64-bit unsigned integer; filter_check returns a boolean

and filter_insert does not return a value, but does modify the SBBF.

The filter_insert operation first uses the most significant 32 bits

of its argument to select a block to operate on. Call the argument

“h”, and recall the use of “z” to mean the number of blocks. Then

a block number i between 0 and z-1 (inclusive) to operate on is

chosen as follows:

unsigned int64 h_top_bits = h >> 32;

unsigned int64 z_as_64_bit = z;

unsigned int32 i = (h_top_bits * z_as_64_bit) >> 32;

The first line extracts the most significant 32 bits from h and

assigns them to a 64-bit unsigned integer. The second line is

simpler: it just sets an unsigned 64-bit value to the same value as

the 32-bit unsigned value z. The purpose of having both h_top_bits

and z_as_64_bit be 64-bit values is so that their product is a

64-bit value. That product is taken in the third line, and then the

most significant 32 bits are extracted into the value i, which is

the index of the block that will be operated on.

After this process to select i, filter_insert uses the least

significant 32 bits of h as the argument to block_insert called on

block i.

The technique for converting the most significant 32 bits to an

integer between 0 and z-1 (inclusive) avoids using the modulo

operation, which is often very slow. This trick can be found in

Kenneth A. Ross’s 2006 IBM research report, “Efficient Hash Probes on

Modern Processors”

The filter_check operation uses the same method as filter_insert

to select a block to operate on, then uses the least significant 32

bits of its argument as an argument to block_check called on that

block, returning the result.

In the pseudocode below, the modulus operator is represented with the C

language’s “%” operator. The “>>” operator is used to denote the

conversion of an unsigned 64-bit integer to an unsigned 32-bit integer

containing only the most significant 32 bits, and C’s cast operator

“(unsigned int32)” is used to denote the conversion of an unsigned

64-bit integer to an unsigned 32-bit integer containing only the least

significant 32 bits.

void filter_insert(SBBF filter, unsigned int64 x) {

unsigned int64 i = ((x >> 32) * filter.numberOfBlocks()) >> 32;

block b = filter.getBlock(i);

block_insert(b, (unsigned int32)x)

}

boolean filter_check(SBBF filter, unsigned int64 x) {

unsigned int64 i = ((x >> 32) * filter.numberOfBlocks()) >> 32;

block b = filter.getBlock(i);

return block_check(b, (unsigned int32)x)

}

The use of blocks is from Putze et al.’s Cache-, Hash- and

Space-Efficient Bloom

filters

To use an SBBF for values of arbitrary Parquet types, we apply a hash

function to that value - at the time of writing,

xxHash, using the function XXH64

with a seed of 0 and following the specification version

0.1.1.

Sizing an SBBF

The check operation in SBBFs can return true for an argument that

was never inserted into the SBBF. These are called “false

positives”. The “false positive probability” is the probability that

any given hash value that was never inserted into the SBBF will

cause check to return true (a false positive). There is not a

simple closed-form calculation of this probability, but here is an

example:

A filter that uses 1024 blocks and has had 26,214 hash values

inserted will have a false positive probability of around 1.26%. Each

of those 1024 blocks occupies 256 bits of space, so the total space

usage is 262,144. That means that the ratio of bits of space to hash

values is 10-to-1. Adding more hash values increases the denominator

and lowers the ratio, which increases the false positive

probability. For instance, inserting twice as many hash values

(52,428) decreases the ratio of bits of space per hash value inserted

to 5-to-1 and increases the false positive probability to

18%. Inserting half as many hash values (13,107) increases the ratio

of bits of space per hash value inserted to 20-to-1 and decreases the

false positive probability to 0.04%.

Here are some sample values of the ratios needed to achieve certain

false positive rates:

Bits of space per insert | False positive probability |

|---|

| 6.0 | 10 % |

| 10.5 | 1 % |

| 16.9 | 0.1 % |

| 26.4 | 0.01 % |

| 41 | 0.001 % |

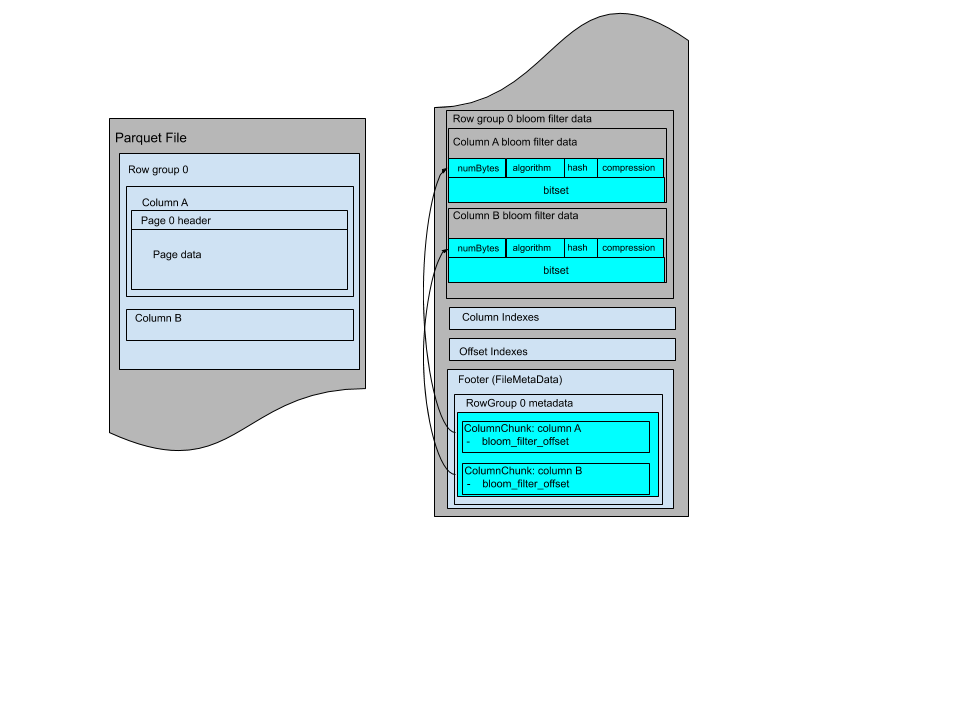

Each multi-block Bloom filter is required to work for only one column chunk. The data of a multi-block

bloom filter consists of the bloom filter header followed by the bloom filter bitset. The bloom filter

header encodes the size of the bloom filter bit set in bytes that is used to read the bitset.

Here are the Bloom filter definitions in thrift:

/** Block-based algorithm type annotation. **/

struct SplitBlockAlgorithm {}

/** The algorithm used in Bloom filter. **/

union BloomFilterAlgorithm {

/** Block-based Bloom filter. **/

1: SplitBlockAlgorithm BLOCK;

}

/** Hash strategy type annotation. xxHash is an extremely fast non-cryptographic hash

* algorithm. It uses 64 bits version of xxHash.

**/

struct XxHash {}

/**

* The hash function used in Bloom filter. This function takes the hash of a column value

* using plain encoding.

**/

union BloomFilterHash {

/** xxHash Strategy. **/

1: XxHash XXHASH;

}

/**

* The compression used in the Bloom filter.

**/

struct Uncompressed {}

union BloomFilterCompression {

1: Uncompressed UNCOMPRESSED;

}

/**

* Bloom filter header is stored at beginning of Bloom filter data of each column

* and followed by its bitset.

**/

struct BloomFilterPageHeader {

/** The size of bitset in bytes **/

1: required i32 numBytes;

/** The algorithm for setting bits. **/

2: required BloomFilterAlgorithm algorithm;

/** The hash function used for Bloom filter. **/

3: required BloomFilterHash hash;

/** The compression used in the Bloom filter **/

4: required BloomFilterCompression compression;

}

struct ColumnMetaData {

...

/** Byte offset from beginning of file to Bloom filter data. **/

14: optional i64 bloom_filter_offset;

}

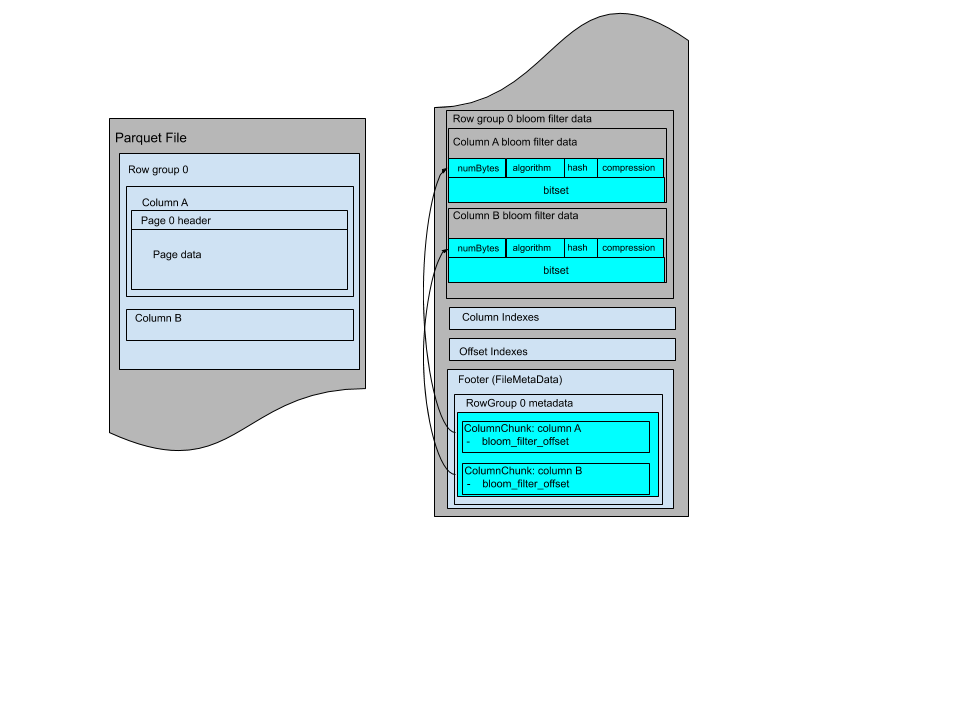

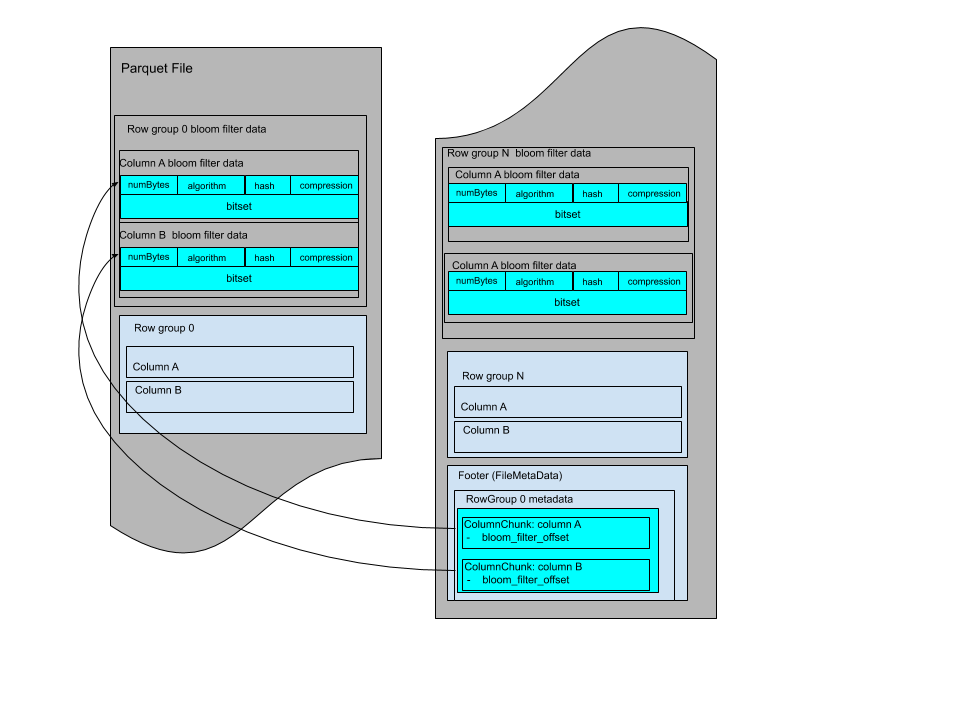

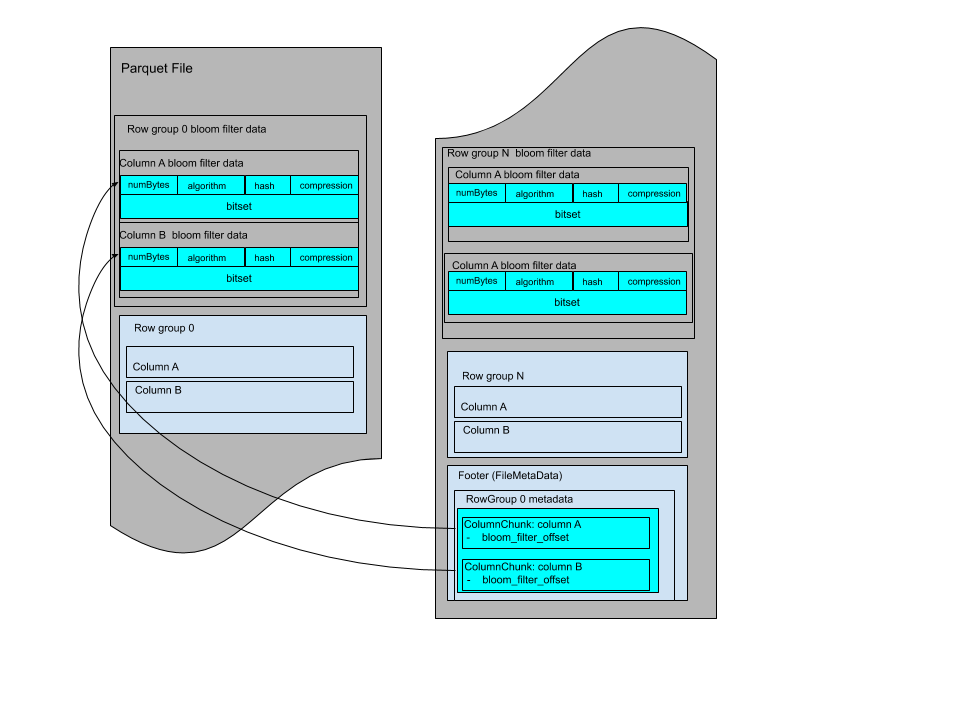

The Bloom filters are grouped by row group and with data for each column in the same order as the file schema.

The Bloom filter data can be stored before the page indexes after all row groups. The file layout looks like:

Or it can be stored between row groups, the file layout looks like:

Encryption

In the case of columns with sensitive data, the Bloom filter exposes a subset of sensitive

information such as the presence of value. Therefore the Bloom filter of columns with sensitive

data should be encrypted with the column key, and the Bloom filter of other (not sensitive) columns

do not need to be encrypted.

Bloom filters have two serializable modules - the PageHeader thrift structure (with its internal

fields, including the BloomFilterPageHeader bloom_filter_page_header), and the Bitset. The header

structure is serialized by Thrift, and written to file output stream; it is followed by the

serialized Bitset.

For Bloom filters in sensitive columns, each of the two modules will be encrypted after

serialization, and then written to the file. The encryption will be performed using the AES GCM

cipher, with the same column key, but with different AAD module types - “BloomFilter Header” (8)

and “BloomFilter Bitset” (9). The length of the encrypted buffer is written before the buffer, as

described in the Parquet encryption specification.

7 - Data Pages

For data pages, the 3 pieces of information are encoded back to back, after the page

header. No padding is allowed in the data page.

In order we have:

- repetition levels data

- definition levels data

- encoded values

The value of uncompressed_page_size specified in the header is for all the 3 pieces combined.

The encoded values for the data page is always required. The definition and repetition levels

are optional, based on the schema definition. If the column is not nested (i.e.

the path to the column has length 1), we do not encode the repetition levels (it would

always have the value 1). For data that is required, the definition levels are

skipped (if encoded, it will always have the value of the max definition level).

For example, in the case where the column is non-nested and required, the data in the

page is only the encoded values.

The supported encodings are described in Encodings.md

The supported compression codecs are described in Compression.md

7.1 - Compression

Overview

Parquet allows the data block inside dictionary pages and data pages to

be compressed for better space efficiency. The Parquet format supports

several compression covering different areas in the compression ratio /

processing cost spectrum.

The detailed specifications of compression codecs are maintained externally

by their respective authors or maintainers, which we reference hereafter.

For all compression codecs except the deprecated LZ4 codec, the raw data

of a (data or dictionary) page is fed as-is to the underlying compression

library, without any additional framing or padding. The information required

for precise allocation of compressed and decompressed buffers is written

in the PageHeader struct.

Codecs

UNCOMPRESSED

No-op codec. Data is left uncompressed.

SNAPPY

A codec based on the

Snappy compression format.

If any ambiguity arises when implementing this format, the implementation

provided by Google Snappy library

is authoritative.

GZIP

A codec based on the GZIP format (not the closely-related “zlib” or “deflate”

formats) defined by RFC 1952.

If any ambiguity arises when implementing this format, the implementation

provided by the zlib compression library is authoritative.

Readers should support reading pages containing multiple GZIP members, however,

as this has historically not been supported by all implementations, it is recommended

that writers refrain from creating such pages by default for better interoperability.

LZO

A codec based on or interoperable with the

LZO compression library.

BROTLI

A codec based on the Brotli format defined by

RFC 7932.

If any ambiguity arises when implementing this format, the implementation

provided by the Brotli compression library

is authoritative.

LZ4

A deprecated codec loosely based on the LZ4 compression algorithm,

but with an additional undocumented framing scheme. The framing is part

of the original Hadoop compression library and was historically copied

first in parquet-mr, then emulated with mixed results by parquet-cpp.

It is strongly suggested that implementors of Parquet writers deprecate

this compression codec in their user-facing APIs, and advise users to

switch to the newer, interoperable LZ4_RAW codec.

ZSTD

A codec based on the Zstandard format defined by

RFC 8478. If any ambiguity arises

when implementing this format, the implementation provided by the

Zstandard compression library

is authoritative.

LZ4_RAW

A codec based on the LZ4 block format.

If any ambiguity arises when implementing this format, the implementation

provided by the LZ4 compression library is authoritative.

7.2 - Encodings

Plain: (PLAIN = 0)

Supported Types: all

This is the plain encoding that must be supported for types. It is

intended to be the simplest encoding. Values are encoded back to back.

The plain encoding is used whenever a more efficient encoding can not be used. It

stores the data in the following format:

- BOOLEAN: Bit Packed, LSB first

- INT32: 4 bytes little endian

- INT64: 8 bytes little endian

- INT96: 12 bytes little endian (deprecated)

- FLOAT: 4 bytes IEEE little endian

- DOUBLE: 8 bytes IEEE little endian

- BYTE_ARRAY: length in 4 bytes little endian followed by the bytes contained in the array

- FIXED_LEN_BYTE_ARRAY: the bytes contained in the array

For native types, this outputs the data as little endian. Floating

point types are encoded in IEEE.

For the byte array type, it encodes the length as a 4 byte little

endian, followed by the bytes.

Dictionary Encoding (PLAIN_DICTIONARY = 2 and RLE_DICTIONARY = 8)

The dictionary encoding builds a dictionary of values encountered in a given column. The

dictionary will be stored in a dictionary page per column chunk. The values are stored as integers

using the RLE/Bit-Packing Hybrid encoding. If the dictionary grows too big, whether in size

or number of distinct values, the encoding will fall back to the plain encoding. The dictionary page is

written first, before the data pages of the column chunk.

Dictionary page format: the entries in the dictionary using the plain encoding.

Data page format: the bit width used to encode the entry ids stored as 1 byte (max bit width = 32),

followed by the values encoded using RLE/Bit packed described above (with the given bit width).

Using the PLAIN_DICTIONARY enum value is deprecated in the Parquet 2.0 specification. Prefer using RLE_DICTIONARY

in a data page and PLAIN in a dictionary page for Parquet 2.0+ files.

Run Length Encoding / Bit-Packing Hybrid (RLE = 3)

This encoding uses a combination of bit-packing and run length encoding to more efficiently store repeated values.

The grammar for this encoding looks like this, given a fixed bit-width known in advance:

rle-bit-packed-hybrid: <length> <encoded-data>

// length is not always prepended, please check the table below for more detail

length := length of the <encoded-data> in bytes stored as 4 bytes little endian (unsigned int32)

encoded-data := <run>*

run := <bit-packed-run> | <rle-run>

bit-packed-run := <bit-packed-header> <bit-packed-values>

bit-packed-header := varint-encode(<bit-pack-scaled-run-len> << 1 | 1)

// we always bit-pack a multiple of 8 values at a time, so we only store the number of values / 8

bit-pack-scaled-run-len := (bit-packed-run-len) / 8

bit-packed-run-len := *see 3 below*

bit-packed-values := *see 1 below*

rle-run := <rle-header> <repeated-value>

rle-header := varint-encode( (rle-run-len) << 1)

rle-run-len := *see 3 below*

repeated-value := value that is repeated, using a fixed-width of round-up-to-next-byte(bit-width)

The bit-packing here is done in a different order than the one in the deprecated bit-packing encoding.

The values are packed from the least significant bit of each byte to the most significant bit,

though the order of the bits in each value remains in the usual order of most significant to least

significant. An example of the encoding is presented below. For comparison, the same case is shown

in the example of the deprecated bit-packing encoding in the next section.

The numbers 1 through 7 using bit width 3:

dec value: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

bit value: 000 001 010 011 100 101 110 111

bit label: ABC DEF GHI JKL MNO PQR STU VWX

would be encoded like this where spaces mark byte boundaries (3 bytes):

bit value: 10001000 11000110 11111010

bit label: HIDEFABC RMNOJKLG VWXSTUPQ

The reason for this packing order is to have fewer word-boundaries on little-endian hardware

when deserializing more than one byte at at time. This is because 4 bytes can be read into a

32 bit register (or 8 bytes into a 64 bit register) and values can be unpacked just by

shifting and ORing with a mask. (to make this optimization work on a big-endian machine,

you would have to use the ordering used in the deprecated bit-packing encoding)

varint-encode() is ULEB-128 encoding, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LEB128

bit-packed-run-len and rle-run-len must be in the range [1, 231 - 1].

This means that a Parquet implementation can always store the run length in a signed

32-bit integer. This length restriction was not part of the Parquet 2.5.0 and earlier

specifications, but longer runs were not readable by the most common Parquet

implementations so, in practice, were not safe for Parquet writers to emit.

Note that the RLE encoding method is only supported for the following types of

data:

- Repetition and definition levels

- Dictionary indices

- Boolean values in data pages, as an alternative to PLAIN encoding

Whether prepending the four-byte length to the encoded-data is summarized as the table below:

+--------------+------------------------+-----------------+

| Page kind | RLE-encoded data kind | Prepend length? |

+--------------+------------------------+-----------------+

| Data page v1 | Definition levels | Y |

| | Repetition levels | Y |

| | Dictionary indices | N |

| | Boolean values | Y |

+--------------+------------------------+-----------------+

| Data page v2 | Definition levels | N |

| | Repetition levels | N |

| | Dictionary indices | N |

| | Boolean values | Y |

+--------------+------------------------+-----------------+

Bit-packed (Deprecated) (BIT_PACKED = 4)

This is a bit-packed only encoding, which is deprecated and will be replaced by the RLE/bit-packing hybrid encoding.

Each value is encoded back to back using a fixed width.

There is no padding between values (except for the last byte, which is padded with 0s).

For example, if the max repetition level was 3 (2 bits) and the max definition level as 3

(2 bits), to encode 30 values, we would have 30 * 2 = 60 bits = 8 bytes.

This implementation is deprecated because the RLE/bit-packing hybrid is a superset of this implementation.

For compatibility reasons, this implementation packs values from the most significant bit to the least significant bit,

which is not the same as the RLE/bit-packing hybrid.

For example, the numbers 1 through 7 using bit width 3:

dec value: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

bit value: 000 001 010 011 100 101 110 111

bit label: ABC DEF GHI JKL MNO PQR STU VWX

would be encoded like this where spaces mark byte boundaries (3 bytes):

bit value: 00000101 00111001 01110111

bit label: ABCDEFGH IJKLMNOP QRSTUVWX

Note that the BIT_PACKED encoding method is only supported for encoding

repetition and definition levels.

Delta Encoding (DELTA_BINARY_PACKED = 5)

Supported Types: INT32, INT64

This encoding is adapted from the Binary packing described in

“Decoding billions of integers per second through vectorization”

by D. Lemire and L. Boytsov.

In delta encoding we make use of variable length integers for storing various

numbers (not the deltas themselves). For unsigned values, we use ULEB128,

which is the unsigned version of LEB128 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LEB128#Unsigned_LEB128).

For signed values, we use zigzag encoding (https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/docs/encoding#signed-integers)

to map negative values to positive ones and apply ULEB128 on the result.

Delta encoding consists of a header followed by blocks of delta encoded values

binary packed. Each block is made of miniblocks, each of them binary packed with its own bit width.

The header is defined as follows:

<block size in values> <number of miniblocks in a block> <total value count> <first value>

- the block size is a multiple of 128; it is stored as a ULEB128 int

- the miniblock count per block is a divisor of the block size such that their

quotient, the number of values in a miniblock, is a multiple of 32; it is

stored as a ULEB128 int

- the total value count is stored as a ULEB128 int

- the first value is stored as a zigzag ULEB128 int

Each block contains

<min delta> <list of bitwidths of miniblocks> <miniblocks>

- the min delta is a zigzag ULEB128 int (we compute a minimum as we need

positive integers for bit packing)

- the bitwidth of each block is stored as a byte

- each miniblock is a list of bit packed ints according to the bit width

stored at the beginning of the block

To encode a block, we will:

Compute the differences between consecutive elements. For the first

element in the block, use the last element in the previous block or, in

the case of the first block, use the first value of the whole sequence,

stored in the header.

Compute the frame of reference (the minimum of the deltas in the block).

Subtract this min delta from all deltas in the block. This guarantees that

all values are non-negative.

Encode the frame of reference (min delta) as a zigzag ULEB128 int followed

by the bit widths of the miniblocks and the delta values (minus the min

delta) bit-packed per miniblock.

Having multiple blocks allows us to adapt to changes in the data by changing

the frame of reference (the min delta) which can result in smaller values

after the subtraction which, again, means we can store them with a lower bit width.

If there are not enough values to fill the last miniblock, we pad the miniblock

so that its length is always the number of values in a full miniblock multiplied

by the bit width. The values of the padding bits should be zero, but readers

must accept paddings consisting of arbitrary bits as well.

If, in the last block, less than <number of miniblocks in a block>

miniblocks are needed to store the values, the bytes storing the bit widths

of the unneeded miniblocks are still present, their value should be zero,

but readers must accept arbitrary values as well. There are no additional

padding bytes for the miniblock bodies though, as if their bit widths were 0

(regardless of the actual byte values). The reader knows when to stop reading

by keeping track of the number of values read.

Subtractions in steps 1) and 2) may incur signed arithmetic overflow, and so

will the corresponding additions when decoding. Overflow should be allowed

and handled as wrapping around in 2’s complement notation so that the original

values are correctly restituted. This may require explicit care in some programming

languages (for example by doing all arithmetic in the unsigned domain).

The following examples use 8 as the block size to keep the examples short,

but in real cases it would be invalid.

Example 1

1, 2, 3, 4, 5

After step 1), we compute the deltas as:

1, 1, 1, 1

The minimum delta is 1 and after step 2, the relative deltas become:

0, 0, 0, 0

The final encoded data is:

header:

8 (block size), 1 (miniblock count), 5 (value count), 1 (first value)

block:

1 (minimum delta), 0 (bitwidth), (no data needed for bitwidth 0)

Example 2

7, 5, 3, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, the deltas would be

-2, -2, -2, 1, 1, 1, 1

The minimum is -2, so the relative deltas are:

0, 0, 0, 3, 3, 3, 3

The encoded data is

header:

8 (block size), 1 (miniblock count), 8 (value count), 7 (first value)

block:

-2 (minimum delta), 2 (bitwidth), 00000011111111b (0,0,0,3,3,3,3 packed on 2 bits)

Characteristics

This encoding is similar to the RLE/bit-packing encoding. However the RLE/bit-packing encoding is specifically used when the range of ints is small over the entire page, as is true of repetition and definition levels. It uses a single bit width for the whole page.

The delta encoding algorithm described above stores a bit width per miniblock and is less sensitive to variations in the size of encoded integers. It is also somewhat doing RLE encoding as a block containing all the same values will be bit packed to a zero bit width thus being only a header.

Delta-length byte array: (DELTA_LENGTH_BYTE_ARRAY = 6)

Supported Types: BYTE_ARRAY

This encoding is always preferred over PLAIN for byte array columns.

For this encoding, we will take all the byte array lengths and encode them using delta

encoding (DELTA_BINARY_PACKED). The byte array data follows all of the length data just

concatenated back to back. The expected savings is from the cost of encoding the lengths

and possibly better compression in the data (it is no longer interleaved with the lengths).

The data stream looks like:

<Delta Encoded Lengths> <Byte Array Data>

For example, if the data was “Hello”, “World”, “Foobar”, “ABCDEF”

then the encoded data would be comprised of the following segments:

- DeltaEncoding(5, 5, 6, 6) (the string lengths)

- “HelloWorldFoobarABCDEF”

Delta Strings: (DELTA_BYTE_ARRAY = 7)

Supported Types: BYTE_ARRAY, FIXED_LEN_BYTE_ARRAY

This is also known as incremental encoding or front compression: for each element in a

sequence of strings, store the prefix length of the previous entry plus the suffix.

For a longer description, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incremental_encoding.

This is stored as a sequence of delta-encoded prefix lengths (DELTA_BINARY_PACKED), followed by

the suffixes encoded as delta length byte arrays (DELTA_LENGTH_BYTE_ARRAY).

For example, if the data was “axis”, “axle”, “babble”, “babyhood”

then the encoded data would be comprised of the following segments:

- DeltaEncoding(0, 2, 0, 3) (the prefix lengths)

- DeltaEncoding(4, 2, 6, 5) (the suffix lengths)

- “axislebabbleyhood”

Note that, even for FIXED_LEN_BYTE_ARRAY, all lengths are encoded despite the redundancy.

Byte Stream Split: (BYTE_STREAM_SPLIT = 9)

Supported Types: FLOAT, DOUBLE

This encoding does not reduce the size of the data but can lead to a significantly better

compression ratio and speed when a compression algorithm is used afterwards.

This encoding creates K byte-streams of length N where K is the size in bytes of the data

type and N is the number of elements in the data sequence. Specifically, K is 4 for FLOAT

type and 8 for DOUBLE type.

The bytes of each value are scattered to the corresponding streams. The 0-th byte goes to the

0-th stream, the 1-st byte goes to the 1-st stream and so on.

The streams are concatenated in the following order: 0-th stream, 1-st stream, etc.

The total length of encoded streams is K * N bytes. Because it does not have any metadata

to indicate the total length, the end of the streams is also the end of data page. No padding

is allowed inside the data page.

Example:

Original data is three 32-bit floats and for simplicity we look at their raw representation.

Element 0 Element 1 Element 2

Bytes AA BB CC DD 00 11 22 33 A3 B4 C5 D6

After applying the transformation, the data has the following representation:

Bytes AA 00 A3 BB 11 B4 CC 22 C5 DD 33 D6

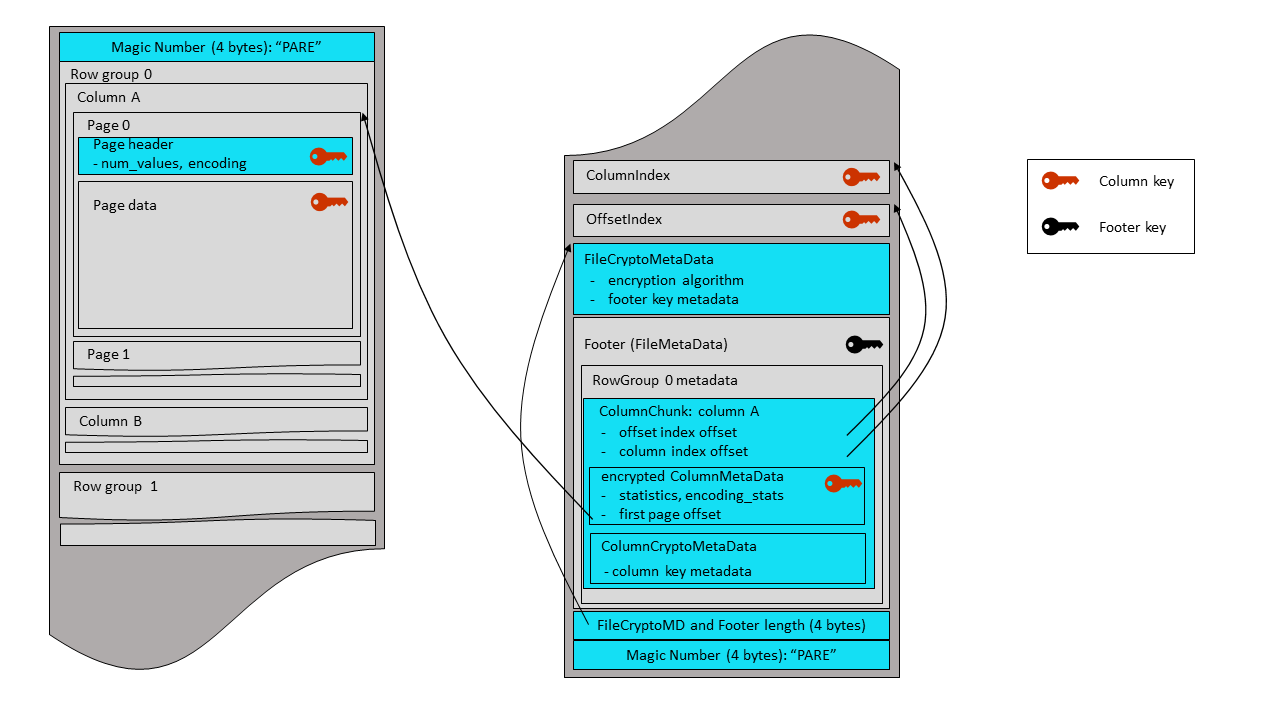

7.3 - Parquet Modular Encryption

Parquet files containing sensitive information can be protected by the modular encryption

mechanism that encrypts and authenticates the file data and metadata - while allowing

for a regular Parquet functionality (columnar projection, predicate pushdown, encoding

and compression).

1 Problem Statement

Existing data protection solutions (such as flat encryption of files, in-storage encryption,

or use of an encrypting storage client) can be applied to Parquet files, but have various

security or performance issues. An encryption mechanism, integrated in the Parquet format,

allows for an optimal combination of data security, processing speed and encryption granularity.

2 Goals

- Protect Parquet data and metadata by encryption, while enabling selective reads

(columnar projection, predicate push-down).

- Implement “client-side” encryption/decryption (storage client). The storage server

must not see plaintext data, metadata or encryption keys.

- Leverage authenticated encryption that allows clients to check integrity of the retrieved

data - making sure the file (or file parts) have not been replaced with a wrong version, or

tampered with otherwise.

- Enable different encryption keys for different columns and for the footer.

- Allow for partial encryption - encrypt only column(s) with sensitive data.

- Work with all compression and encoding mechanisms supported in Parquet.

- Support multiple encryption algorithms, to account for different security and performance

requirements.

- Enable two modes for metadata protection -

- full protection of file metadata

- partial protection of file metadata that allows legacy readers to access unencrypted

columns in an encrypted file.

- Minimize overhead of encryption - in terms of size of encrypted files, and throughput

of write/read operations.

3 Technical Approach

Parquet files are comprised of separately serialized components: pages, page headers, column

indexes, offset indexes, bloom filter headers and bitsets, the footer. Parquet encryption

mechanism denotes them as “modules”

and encrypts each module separately – making it possible to fetch and decrypt the footer,

find the offset of required pages, fetch the pages and decrypt the data. In this document,

the term “footer” always refers to the regular Parquet footer - the FileMetaData structure,

and its nested fields (row groups / column chunks).

File encryption is flexible - each column and the footer can be encrypted with the same key,

with a different key, or not encrypted at all.

The results of compression of column pages are encrypted before being written to the output

stream. A new Thrift structure, with column crypto metadata, is added to column chunks of

the encrypted columns. This metadata provides information about the column encryption keys.

The results of serialization of Thrift structures are encrypted, before being written

to the output stream.

The file footer can be either encrypted or left as a plaintext. In an encrypted footer mode,

a new Thrift structure with file crypto metadata is added to the file. This metadata provides

information about the file encryption algorithm and the footer encryption key.

In a plaintext footer mode, the contents of the footer structure is visible and signed

in order to verify its integrity. New footer fields keep an

information about the file encryption algorithm and the footer signing key.

For encrypted columns, the following modules are always encrypted, with the same column key:

pages and page headers (both dictionary and data), column indexes, offset indexes, bloom filter

headers and bitsets. If the

column key is different from the footer encryption key, the column metadata is serialized

separately and encrypted with the column key. In this case, the column metadata is also

considered to be a module.

4 Encryption Algorithms and Keys

Parquet encryption algorithms are based on the standard AES ciphers for symmetric encryption.

AES is supported in Intel and other CPUs with hardware acceleration of crypto operations

(“AES-NI”) - that can be leveraged, for example, by Java programs (automatically via HotSpot),

or C++ programs (via EVP-* functions in OpenSSL). Parquet supports all standard AES key sizes:

128, 192 and 256 bits.

Initially, two algorithms have been implemented, one based on a GCM mode of AES, and the

other on a combination of GCM and CTR modes.

4.1 AES modes used in Parquet

4.1.1 AES GCM

AES GCM is an authenticated encryption. Besides the data confidentiality (encryption), it

supports two levels of integrity verification (authentication): of the data (default),

and of the data combined with an optional AAD (“additional authenticated data”). The

authentication allows to make sure the data has not been tampered with. An AAD

is a free text to be authenticated, together with the data. The user can, for example, pass the

file name with its version (or creation timestamp) as an AAD input, to verify that the

file has not been replaced with an older version. The details on how Parquet creates

and uses AADs are provided in the section 4.4.

4.1.2 AES CTR

AES CTR is a regular (not authenticated) cipher. It is faster than the GCM cipher, since it

doesn’t perform integrity verification and doesn’t calculate an authentication tag.

Actually, GCM is a combination of the CTR cipher and an

authentication layer called GMAC. For applications running without AES acceleration

(e.g. on Java versions before Java 9) and willing to compromise on content verification,

CTR cipher can provide a boost in encryption/decryption throughput.

4.1.3 Nonces and IVs

GCM and CTR ciphers require a unique vector to be provided for each encrypted stream.

In this document, the unique input to GCM encryption is called nonce (“number used once”).

The unique input to CTR encryption is called IV (“initialization vector”), and is comprised of two

parts: a nonce and an initial counter field.

Parquet encryption uses the RBG-based (random bit generator) nonce construction as defined in

the section 8.2.2 of the NIST SP 800-38D document. For each encrypted module, Parquet generates a

unique nonce with a length of 12 bytes (96 bits). Notice: the NIST

specification uses a term “IV” for what is called “nonce” in the Parquet encryption design.

4.2 Parquet encryption algorithms

4.2.1 AES_GCM_V1

This Parquet algorithm encrypts all modules by the GCM cipher, without padding. The AES GCM cipher

must be implemented by a cryptographic provider according to the NIST SP 800-38D specification.

In Parquet, an input to the GCM cipher is an encryption key, a 12-byte nonce, a plaintext and an

AAD. The output is a ciphertext with the length equal to that of plaintext, and a 16-byte authentication

tag used to verify the ciphertext and AAD integrity.

4.2.2 AES_GCM_CTR_V1

In this Parquet algorithm, all modules except pages are encrypted with the GCM cipher, as described

above. The pages are encrypted by the CTR cipher without padding. This allows to encrypt/decrypt

the bulk of the data faster, while still verifying the metadata integrity and making

sure the file has not been replaced with a wrong version. However, tampering with the

page data might go unnoticed. The AES CTR cipher

must be implemented by a cryptographic provider according to the NIST SP 800-38A specification.

In Parquet, an input to the CTR cipher is an encryption key, a 16-byte IV and a plaintext. IVs are comprised of

a 12-byte nonce and a 4-byte initial counter field. The first 31 bits of the initial counter field are set

to 0, the last bit is set to 1. The output is a ciphertext with the length equal to that of plaintext.

A wide variety of services and tools for management of encryption keys exist in the

industry today. Public clouds offer different key management services (KMS), and

organizational IT systems either build proprietary key managers in-house or adopt open source

tools for on-premises deployment. Besides the diversity of management tools, there are many

ways to generate and handle the keys themselves (generate Data keys inside KMS – or locally

upon data encryption; use Data keys only, or use Master keys to encrypt the Data keys;

store the encrypted key material inside the data file, or at a separate location; etc). There

is also a large variety of authorization and certification methods, required to control the

access to encryption keys.

Parquet is not limited to a single KMS, key generation/wrapping method, or authorization service.

Instead, Parquet provides a developer with a simple interface that can be utilized for implementation

of any key management scheme. For each column or footer key, a file writer can generate and pass an

arbitrary key_metadata byte array that will be stored in the file. This field is made available to

file readers to enable recovery of the key. For example, the key_metadata

can keep a serialized

- String ID of a Data key. This enables direct retrieval of the Data key from a KMS.

- Encrypted Data key, and string ID of a Master key. The Data key is generated randomly and

encrypted with a Master key either remotely in a KMS, or locally after retrieving the Master key from a KMS.

Master key rotation requires modification of the data file footer.

- Short ID (counter) of a Data key inside the Parquet data file. The Data key is encrypted with a

Master key using one of the options described above – but the resulting key material is stored

separately, outside the data file, and will be retrieved using the counter and file path.

Master key rotation doesn’t require modification of the data file.

Key metadata can also be empty - in a case the encryption keys are fully managed by the caller

code, and passed explicitly to Parquet readers for the file footer and each encrypted column.

4.4 Additional Authenticated Data

The AES GCM cipher protects against byte replacement inside a ciphertext - but, without an AAD,

it can’t prevent replacement of one ciphertext with another (encrypted with the same key).

Parquet modular encryption leverages AADs to protect against swapping ciphertext modules (encrypted

with AES GCM) inside a file or between files. Parquet can also protect against swapping full

files - for example, replacement of a file with an old version, or replacement of one table

partition with another. AADs are built to reflects the identity of a file and of the modules

inside the file.

Parquet constructs a module AAD from two components: an optional AAD prefix - a string provided

by the user for the file, and an AAD suffix, built internally for each GCM-encrypted module

inside the file. The AAD prefix should reflect the target identity that helps to detect file

swapping (a simple example - table name with a date and partition, e.g. “employees_23May2018.part0”).

The AAD suffix reflects the internal identity of modules inside the file, which for example

prevents replacement of column pages in row group 0 by pages from the same column in row

group 1. The module AAD is a direct concatenation of the prefix and suffix parts.

4.4.1 AAD prefix

File swapping can be prevented by an AAD prefix string, that uniquely identifies the file and

allows to differentiate it e.g. from older versions of the file or from other partition files in the same

data set (table). This string is optionally passed by a writer upon file creation. If provided,

the AAD prefix is stored in an aad_prefix field in the file, and is made available to the readers.

This field is not encrypted. If a user is concerned about keeping the file identity inside the file,

the writer code can explicitly request Parquet not to store the AAD prefix. Then the aad_prefix field

will be empty; AAD prefixes must be fully managed by the caller code and supplied explicitly to Parquet

readers for each file.

The protection against swapping full files is optional. It is not enabled by default because

it requires the writers to generate and pass an AAD prefix.

A reader of a file created with an AAD prefix, should be able to verify the prefix (file identity)

by comparing it with e.g. the target table name, using a convention accepted in the organization.

Readers of data sets, comprised of multiple partition files, can verify data set integrity by

checking the number of files and the AAD prefix of each file. For example, a reader that needs to

process the employee table, a May 23 version, knows (via the convention) that

the AAD prefix must be “employees_23May2018.partN” in

each corresponding table file. If a file AAD prefix is “employees_23May2018.part0”, the reader

will know it is fine, but if the prefix is “employees_23May2016.part0” or “contractors_23May2018.part0” -

the file is wrong. The reader should also know the number of table partitions and verify availability

of all partition files (prefixes) from 0 to N-1.

4.4.2 AAD suffix

The suffix part of a module AAD protects against module swapping inside a file. It also protects against

module swapping between files - in situations when an encryption key is re-used in multiple files and the

writer has not provided a unique AAD prefix for each file.

Unlike AAD prefix, a suffix is built internally by Parquet, by direct concatenation of the following parts:

- [All modules] internal file identifier - a random byte array generated for each file (implementation-defined length)

- [All modules] module type (1 byte)

- [All modules except footer] row group ordinal (2 byte short, little endian)

- [All modules except footer] column ordinal (2 byte short, little endian)

- [Data page and header only] page ordinal (2 byte short, little endian)

The following module types are defined:

- Footer (0)

- ColumnMetaData (1)

- Data Page (2)

- Dictionary Page (3)

- Data PageHeader (4)

- Dictionary PageHeader (5)

- ColumnIndex (6)

- OffsetIndex (7)

- BloomFilter Header (8)

- BloomFilter Bitset (9)

| Internal File ID | Module type | Row group ordinal | Column ordinal | Page ordinal |

|---|

| Footer | yes | yes (0) | no | no | no |

| ColumnMetaData | yes | yes (1) | yes | yes | no |

| Data Page | yes | yes (2) | yes | yes | yes |

| Dictionary Page | yes | yes (3) | yes | yes | no |

| Data PageHeader | yes | yes (4) | yes | yes | yes |

| Dictionary PageHeader | yes | yes (5) | yes | yes | no |

| ColumnIndex | yes | yes (6) | yes | yes | no |

| OffsetIndex | yes | yes (7) | yes | yes | no |

| BloomFilter Header | yes | yes (8) | yes | yes | no |

| BloomFilter Bitset | yes | yes (9) | yes | yes | no |

5.1 Encrypted module serialization

All modules, except column pages, are encrypted with the GCM cipher. In the AES_GCM_V1 algorithm,

the column pages are also encrypted with AES GCM. For each module, the GCM encryption

buffer is comprised of a nonce, ciphertext and tag, described in the Algorithms section. The length of

the encryption buffer (a 4-byte little endian) is written to the output stream, followed by the buffer itself.

| length (4 bytes) | nonce (12 bytes) | ciphertext (length-28 bytes) | tag (16 bytes) |

|---|

In the AES_GCM_CTR_V1 algorithm, the column pages are encrypted with AES CTR.

For each page, the CTR encryption buffer is comprised of a nonce and ciphertext,

described in the Algorithms section. The length of the encryption buffer

(a 4-byte little endian) is written to the output stream, followed by the buffer itself.

| length (4 bytes) | nonce (12 bytes) | ciphertext (length-12 bytes) |

|---|

5.2 Crypto structures

Parquet file encryption algorithm is specified in a union of the following Thrift structures:

struct AesGcmV1 {

/** AAD prefix **/

1: optional binary aad_prefix

/** Unique file identifier part of AAD suffix **/

2: optional binary aad_file_unique

/** In files encrypted with AAD prefix without storing it,

* readers must supply the prefix **/

3: optional bool supply_aad_prefix

}

struct AesGcmCtrV1 {

/** AAD prefix **/

1: optional binary aad_prefix

/** Unique file identifier part of AAD suffix **/

2: optional binary aad_file_unique

/** In files encrypted with AAD prefix without storing it,

* readers must supply the prefix **/

3: optional bool supply_aad_prefix

}

union EncryptionAlgorithm {

1: AesGcmV1 AES_GCM_V1

2: AesGcmCtrV1 AES_GCM_CTR_V1

}

If a writer provides an AAD prefix, it will be used for enciphering the file and stored in the

aad_prefix field. However, the writer can request Parquet not to store the prefix in the file. In

this case, the aad_prefix field will not be set, and the supply_aad_prefix field will be set

to true to inform readers they must supply the AAD prefix for this file in order to be able to

decrypt it.

The row group ordinal, required for AAD suffix calculation, is set in the RowGroup structure:

struct RowGroup {

...

/** Row group ordinal in the file **/

7: optional i16 ordinal

}

A crypto_metadata field is set in each ColumnChunk in the encrypted columns. ColumnCryptoMetaData

is a union - the actual structure is chosen depending on whether the column is encrypted with the

footer encryption key, or with a column-specific key. For the latter, a key metadata can be specified.

struct EncryptionWithFooterKey {

}

struct EncryptionWithColumnKey {

/** Column path in schema **/

1: required list<string> path_in_schema

/** Retrieval metadata of column encryption key **/

2: optional binary key_metadata

}

union ColumnCryptoMetaData {

1: EncryptionWithFooterKey ENCRYPTION_WITH_FOOTER_KEY

2: EncryptionWithColumnKey ENCRYPTION_WITH_COLUMN_KEY

}

struct ColumnChunk {

...

/** Crypto metadata of encrypted columns **/

8: optional ColumnCryptoMetaData crypto_metadata

}

The Parquet file footer, and its nested structures, contain sensitive information - ranging

from a secret data (column statistics) to other information that can be exploited by an

attacker (e.g. schema, num_values, key_value_metadata, encoding

and crypto_metadata). This information is automatically protected when the footer and

secret columns are encrypted with the same key. In other cases - when column(s) and the

footer are encrypted with different keys; or column(s) are encrypted and the footer is not,

an extra measure is required to protect the column-specific information in the file footer.

In these cases, the ColumnMetaData structures are Thrift-serialized separately and encrypted

with a column-specific key, thus protecting the column stats and

other metadata. The column metadata module is encrypted with the GCM cipher, serialized

according to the section 5.1 instructions and stored in an optional binary encrypted_column_metadata

field in the ColumnChunk.

struct ColumnChunk {

...

/** Column metadata for this chunk.. **/

3: optional ColumnMetaData meta_data

..

/** Crypto metadata of encrypted columns **/

8: optional ColumnCryptoMetaData crypto_metadata

/** Encrypted column metadata for this chunk **/

9: optional binary encrypted_column_metadata

}

In files with sensitive column data, a good security practice is to encrypt not only the

secret columns, but also the file footer metadata. This hides the file schema,

number of rows, key-value properties, column sort order, names of the encrypted columns

and metadata of the column encryption keys.

The columns encrypted with the same key as the footer must leave the column metadata at the original

location, optional ColumnMetaData meta_data in the ColumnChunk structure.

This field is not set for columns encrypted with a column-specific key - instead, the ColumnMetaData

is Thrift-serialized, encrypted with the column key and written to the encrypted_column_metadata

field in the ColumnChunk structure, as described in the section 5.3.

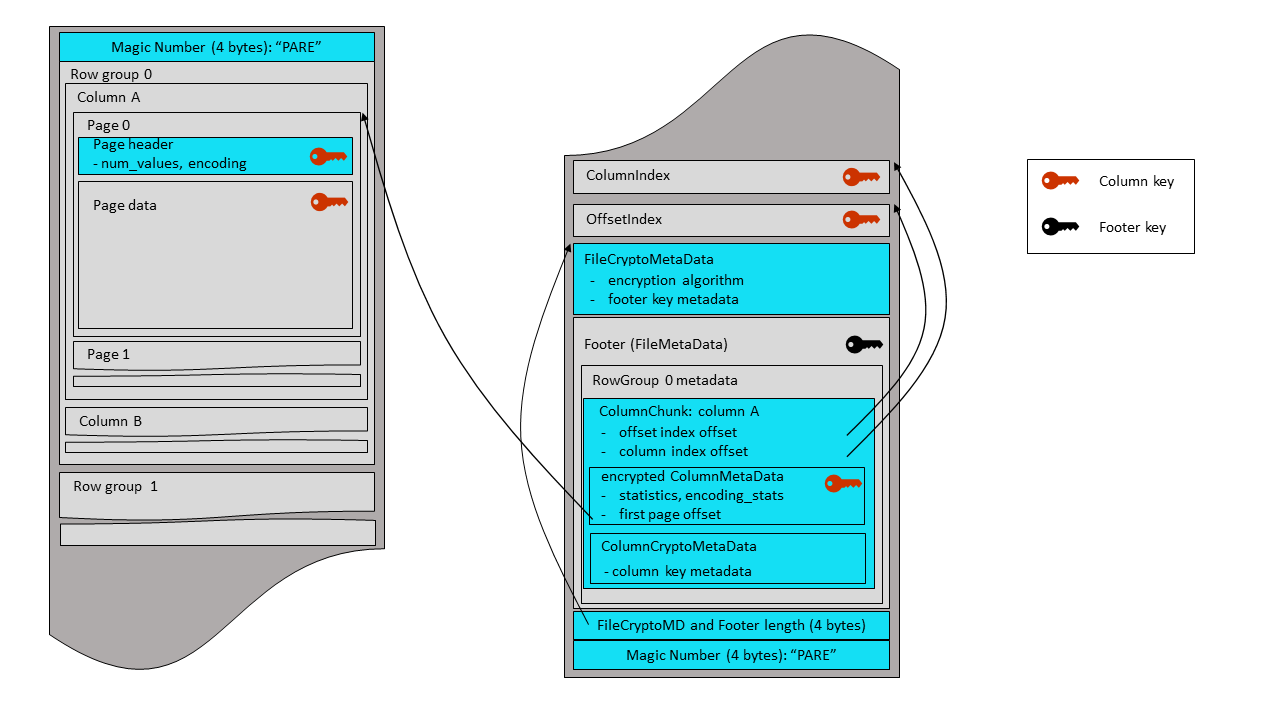

A Thrift-serialized FileCryptoMetaData structure is written before the encrypted footer.

It contains information on the file encryption algorithm and on the footer key metadata. Then

the combined length of this structure and of the encrypted footer is written as a 4-byte

little endian integer, followed by a final magic string, “PARE”. The same magic bytes are

written at the beginning of the file (offset 0). Parquet readers start file parsing by

reading and checking the magic string. Therefore, the encrypted footer mode uses a new

magic string (“PARE”) in order to instruct readers to look for a file crypto metadata

before the footer - and also to immediately inform legacy readers (expecting ‘PAR1’

bytes) that they can’t parse this file.

/** Crypto metadata for files with encrypted footer **/

struct FileCryptoMetaData {

/**

* Encryption algorithm. This field is only used for files

* with encrypted footer. Files with plaintext footer store algorithm id

* inside footer (FileMetaData structure).

*/

1: required EncryptionAlgorithm encryption_algorithm

/** Retrieval metadata of key used for encryption of footer,

* and (possibly) columns **/

2: optional binary key_metadata

}

This mode allows legacy Parquet versions (released before the encryption support) to access

unencrypted columns in encrypted files - at a price of leaving certain metadata fields

unprotected in these files.

The plaintext footer mode can be useful during a transitional period in organizations where

some frameworks can’t be upgraded to a new Parquet library for a while. Data writers will

upgrade and run with a new Parquet version, producing encrypted files in this mode. Data

readers working with sensitive data will also upgrade to a new Parquet library. But other

readers that don’t need the sensitive columns, can continue working with an older Parquet

version. They will be able to access plaintext columns in encrypted files. A legacy reader,

trying to access a sensitive column data in an encrypted file with a plaintext footer, will

get an exception. More specifically, a Thrift parsing exception on an encrypted page header

structure. Again, using legacy Parquet readers for encrypted files is a temporary solution.

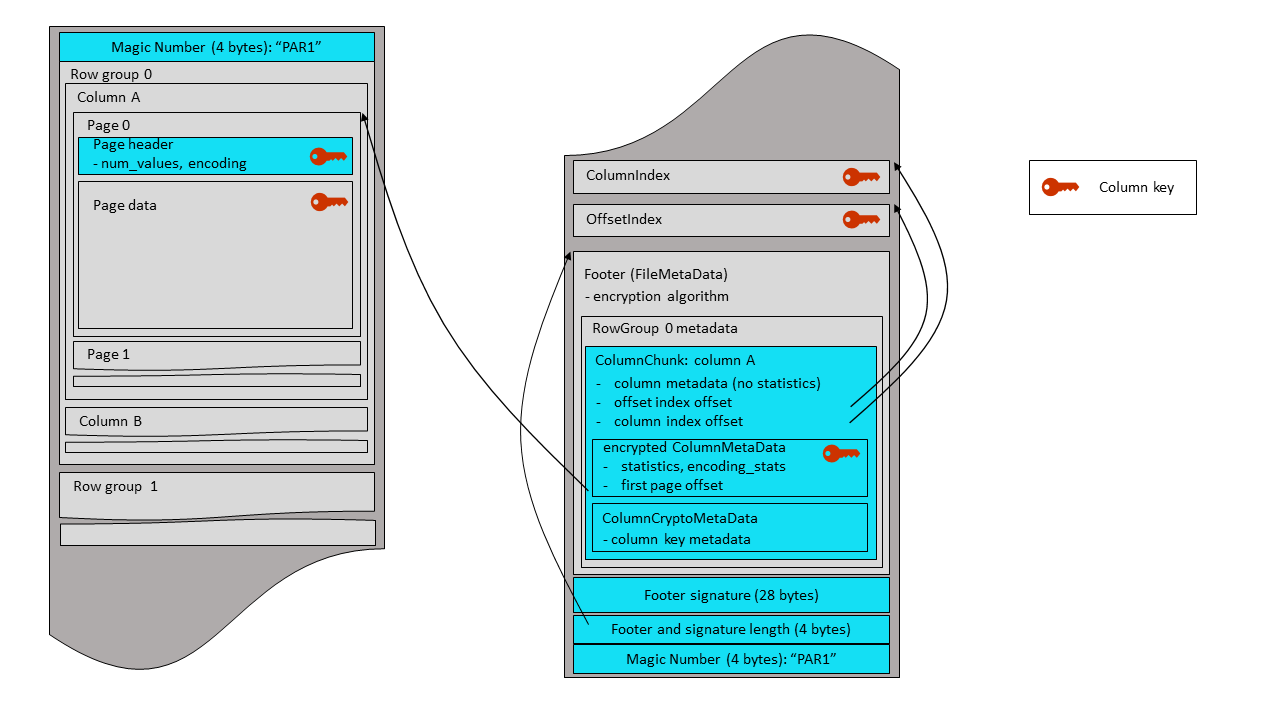

In the plaintext footer mode, the optional ColumnMetaData meta_data is set in the ColumnChunk

structure for all columns, but is stripped of the statistics for the sensitive (encrypted)

columns. These statistics are available for new readers with the column key - they decrypt

the encrypted_column_metadata field, described in the section 5.3, and parse it to get statistics

and all other column metadata values. The legacy readers are not aware of the encrypted metadata field;

they parse the regular (plaintext) field as usual. While they can’t read the data of encrypted

columns, they read their metadata to extract the offset and size of encrypted column data,

required for column chunk vectorization.

The plaintext footer is signed in order to prevent tampering with the

FileMetaData contents. The footer signing is done by encrypting the serialized FileMetaData

structure with the

AES GCM algorithm - using a footer signing key, and an AAD constructed according to the instructions

of the section 4.4. Only the nonce and GCM tag are stored in the file – as a 28-byte

fixed-length array, written right after the footer itself. The ciphertext is not stored,

because it is not required for footer integrity verification by readers.

| nonce (12 bytes) | tag (16 bytes) |

|---|

The plaintext footer mode sets the following fields in the the FileMetaData structure:

struct FileMetaData {

...

/**

* Encryption algorithm. This field is set only in encrypted files

* with plaintext footer. Files with encrypted footer store algorithm id

* in FileCryptoMetaData structure.

*/

8: optional EncryptionAlgorithm encryption_algorithm

/**

* Retrieval metadata of key used for signing the footer.

* Used only in encrypted files with plaintext footer.

*/

9: optional binary footer_signing_key_metadata

}

The FileMetaData structure is Thrift-serialized and written to the output stream.

The 28-byte footer signature is written after the plaintext footer, followed by a 4-byte little endian integer

that contains the combined length of the footer and its signature. A final magic string,

“PAR1”, is written at the end of the

file. The same magic string is written at the beginning of the file (offset 0). The magic bytes

for plaintext footer mode are ‘PAR1’ to allow legacy readers to read projections of the file

that do not include encrypted columns.

6. Encryption Overhead

The size overhead of Parquet modular encryption is negligible, since most of the encryption

operations are performed on pages (the minimal unit of Parquet data storage and compression).

The overhead order of magnitude is adding 1 byte per each ~30,000 bytes of original

data - calculated by comparing the page encryption overhead (nonce + tag + length = 32 bytes)

to the default page size (1 MB). This is a rough estimation, and can change with the encryption

algorithm (no 16-byte tag in AES_GCM_CTR_V1) and with page configuration or data encoding/compression.

The throughput overhead of Parquet modular encryption depends on whether AES enciphering is

done in software or hardware. In both cases, performing encryption on full pages (~1MB buffers)

instead of on much smaller individual data values causes AES to work at its maximal speed.

7.4 - Checksumming

Pages of all kinds can be individually checksummed. This allows disabling of checksums

at the HDFS file level, to better support single row lookups. Checksums are calculated

using the standard CRC32 algorithm - as used in e.g. GZip - on the serialized binary

representation of a page (not including the page header itself).

7.5 - Column Chunks

Column chunks are composed of pages written back to back. The pages share a common

header and readers can skip over pages they are not interested in. The data for the

page follows the header and can be compressed and/or encoded. The compression and

encoding is specified in the page metadata.

A column chunk might be partly or completely dictionary encoded. It means that

dictionary indexes are saved in the data pages instead of the actual values. The

actual values are stored in the dictionary page. See details in Encodings.md.

The dictionary page must be placed at the first position of the column chunk. At

most one dictionary page can be placed in a column chunk.

Additionally, files can contain an optional column index to allow readers to

skip pages more efficiently. See PageIndex.md for details and

the reasoning behind adding these to the format.

7.6 - Error Recovery

If the file metadata is corrupt, the file is lost. If the column metadata is corrupt,

that column chunk is lost (but column chunks for this column in other row groups are

okay). If a page header is corrupt, the remaining pages in that chunk are lost. If

the data within a page is corrupt, that page is lost. The file will be more

resilient to corruption with smaller row groups.

Potential extension: With smaller row groups, the biggest issue is placing the file

metadata at the end. If an error happens while writing the file metadata, all the

data written will be unreadable. This can be fixed by writing the file metadata

every Nth row group.

Each file metadata would be cumulative and include all the row groups written so

far. Combining this with the strategy used for rc or avro files using sync markers,

a reader could recover partially written files.

8 - Nulls

Nullity is encoded in the definition levels (which is run-length encoded). NULL values

are not encoded in the data. For example, in a non-nested schema, a column with 1000 NULLs

would be encoded with run-length encoding (0, 1000 times) for the definition levels and

nothing else.

9 - Page Index

This document describes the format for column index pages in the Parquet

footer. These pages contain statistics for DataPages and can be used to skip

pages when scanning data in ordered and unordered columns.

Problem Statement

In previous versions of the format, Statistics are stored for ColumnChunks in

ColumnMetaData and for individual pages inside DataPageHeader structs. When

reading pages, a reader had to process the page header to determine

whether the page could be skipped based on the statistics. This means the reader

had to access all pages in a column, thus likely reading most of the column

data from disk.

Goals

- Make both range scans and point lookups I/O efficient by allowing direct

access to pages based on their min and max values. In particular:

- A single-row lookup in a row group based on the sort column of that row group

will only read one data page per the retrieved column.

- Range scans on the sort column will only need to read the exact data

pages that contain relevant data.

- Make other selective scans I/O efficient: if we have a very selective

predicate on a non-sorting column, for the other retrieved columns we

should only need to access data pages that contain matching rows.

- No additional decoding effort for scans without selective predicates, e.g.,

full-row group scans. If a reader determines that it does not need to read

the index data, it does not incur any overhead.

- Index pages for sorted columns use minimal storage by storing only the

boundary elements between pages.

Non-Goals

- Support for the equivalent of secondary indices, i.e., an index structure

sorted on the key values over non-sorted data.

Technical Approach

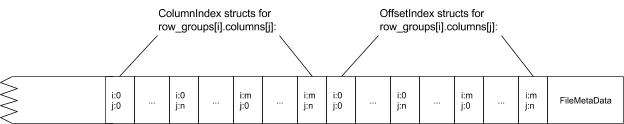

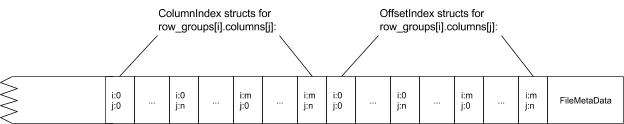

We add two new per-column structures to the row group metadata:

- ColumnIndex: this allows navigation to the pages of a column based on column

values and is used to locate data pages that contain matching values for a

scan predicate

- OffsetIndex: this allows navigation by row index and is used to retrieve

values for rows identified as matches via the ColumnIndex. Once rows of a

column are skipped, the corresponding rows in the other columns have to be

skipped. Hence the OffsetIndexes for each column in a RowGroup are stored

together.

The new index structures are stored separately from RowGroup, near the footer.

This is done so that a reader does not have to pay the I/O and deserialization

cost for reading them if it is not doing selective scans. The index structures'

location and length are stored in ColumnChunk.

Some observations:

- We don’t need to record the lower bound for the first page and the upper

bound for the last page, because the row group Statistics can provide that.

We still include those for the sake of uniformity, and the overhead should be

negligible.

- We store lower and upper bounds for the values of each page. These may be the

actual minimum and maximum values found on a page, but can also be (more

compact) values that do not exist on a page. For example, instead of storing

““Blart Versenwald III”, a writer may set

min_values[i]="B",

max_values[i]="C". This allows writers to truncate large values and writers

should use this to enforce some reasonable bound on the size of the index

structures. - Readers that support ColumnIndex should not also use page statistics. The

only reason to write page-level statistics when writing ColumnIndex structs

is to support older readers (not recommended).

For ordered columns, this allows a reader to find matching pages by performing

a binary search in min_values and max_values. For unordered columns, a

reader can find matching pages by sequentially reading min_values and

max_values.

For range scans, this approach can be extended to return ranges of rows, page

indices, and page offsets to scan in each column. The reader can then

initialize a scanner for each column and fast forward them to the start row of

the scan.

The min_values and max_values are calculated based on the column_orders

field in the FileMetaData struct of the footer.

10 - Implementation status

This page summarizes the features supported by different Parquet

implementations.

Note: If you find out of date information, please help us improve the accuracy

of this page by opening an issue or submitting a pull request.

Legend

The value in each box means:

- ✅: supported

- ❌: not supported

- (R/W): partial reader/writer only support

- (blank): no data

Implementations:

Physical types

Physical types are defined by the enum Type in parquet.thrift

| Data type | arrow | parquet-java | arrow-go | arrow-rs | cudf | hyparquet | duckdb |

|---|

| BOOLEAN | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| INT32 | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| INT64 | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| INT96 (1) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | (R) |

| FLOAT | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| DOUBLE | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| BYTE_ARRAY | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| FIXED_LEN_BYTE_ARRAY | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

- (1) This type is deprecated, but as of 2024 it’s common in currently produced parquet files

Logical types

Logical types are defined by the union LogicalType in parquet.thrift and described in LogicalTypes.md

| Data type | arrow | parquet-java | arrow-go | arrow-rs | cudf | hyparquet | duckdb |

|---|

| STRING | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| ENUM | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ (1) | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| UUID | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ (1) | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| 8, 16, 32, 64 bit signed and unsigned INT | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| DECIMAL (INT32) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| DECIMAL (INT64) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| DECIMAL (BYTE_ARRAY) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) |

| DECIMAL (FIXED_LEN_BYTE_ARRAY) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| FLOAT16 | ✅ | ✅ (1) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| DATE | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| TIME (INT32) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| TIME (INT64) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| TIMESTAMP (INT64) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| INTERVAL | ✅ | ✅ (1) | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| JSON | ✅ | ✅ (1) | ✅ | ✅ (1) | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| BSON | ❌ | ✅ (1) | ✅ | ✅ (1) | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| VARIANT | | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| GEOMETRY | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| GEOGRAPHY | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| LIST | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | ✅ |

| MAP | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | ✅ |

| UNKNOWN (always null) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

- (1) Only supported to use its annotated physical type

Encodings

Encodings are defined by the enum Encoding in parquet.thrift and described in Encodings.md

| Encoding | arrow | parquet-java | arrow-go | arrow-rs | cudf | hyparquet | duckdb |

|---|

| PLAIN | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| PLAIN_DICTIONARY | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) |

| RLE_DICTIONARY | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| RLE | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| BIT_PACKED (deprecated) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ (1) | (R) | (R) | ❌ |

| DELTA_BINARY_PACKED | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | ✅ |

| DELTA_LENGTH_BYTE_ARRAY | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | ✅ |

| DELTA_BYTE_ARRAY | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | ✅ |

| BYTE_STREAM_SPLIT | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | ✅ |

- (1) Partial read support, but only in the case of level data with a bitwidth of 0

Compressions

Compressions are defined by the enum CompressionCodec in parquet.thrift and described in Compression.md

| Compression | arrow | parquet-java | arrow-go | arrow-rs | cudf | hyparquet | duckdb |

|---|

| UNCOMPRESSED | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| BROTLI | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | (R) | ✅ |

| GZIP | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | (R) | ✅ |

| LZ4 (deprecated) | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | (R) | ❌ |

| LZ4_RAW | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | ✅ |

| LZO | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| SNAPPY | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| ZSTD | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | ✅ |

| Feature | arrow | parquet-java | arrow-go | arrow-rs | cudf | hyparquet | duckdb |

|---|

| xxHash-based bloom filters | (R) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | | ✅ |

| Bloom filter length (1) | (R) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | | ✅ |

| Statistics min_value, max_value | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Page index | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | (R) |

| Page CRC32 checksum | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | (R) |

| Modular encryption | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ (*) |

| Size statistics (2) | ✅ | ✅ | (R) | ✅ | ✅ | | (R) |

| Data Page V2 (3) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

High level data APIs for Parquet feature usage

| Feature | arrow | parquet-java | arrow-go | arrow-rs | cudf | hyparquet | duckdb |

|---|

| External column data (1) | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | (W) | ✅ | ❌ |

| Row group “Sorting column” metadata (2) | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | (W) | ❌ | (R) |

| Row group pruning using statistics | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ (*) | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Row group pruning using bloom filter | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ (*) | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Reading select columns only | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Page pruning using statistics | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ (*) | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |